Where’s the music coming from?

I’ve shared a few songs and sketches in previous entries on Substack. Friends didn’t know I made music as a hobby. I haven’t done it in a long time. Making music is something I thought I’d abandoned, throwing all-in on writing since moving to San Francisco.

But closing in on 49, I’m playing and recording again.

Like a lot of writers, I’ve always written to music. Novels, scripts, this essay. The longer form writing accumulates its own playlist. The playlist becomes a “room” for the project, a familiar emotional space, transforming coffee shops and filtering out plane cabins. The music negates enough of the self and makes the world more manageable, moderating high degrees of self-consciousness. I’m here and I’m not here.

Always was a self-conscious kid. Got my first Sony Walkman around 1983, the silver brick with the orange felt headphones. I wore it on the bus home from school, a full hour-and-a-half one way. In the late afternoon I ran through the woods by myself, shouting Run DMC lyrics. At home waited my prized boom box, almighty tool for dubbing songs off the radio, the glorious FM broadcast compression and BASF tape hiss merging to lay a plush bed for the songs. The noise was so powerful it was almost a smell.

But I wasn’t a musician. I was a writer. Writing was what I liked to do, the zone where teachers and friends encouraged me. My brother, Bryan, was always musician and still is. He began with classical guitar, quickly moved into an electric, played with post-punk and hardcore bands, and now plays his own strain of singer/songwriter acoustic.

Yet I prized electropop and rap music and did get a Casio keyboard at some point. All those cheap Casios and Yamahas of the 1980s were as prevalent as Speak & Spells, used more often as toys than genuine instruments. My best friend, Ryan, began teaching himself guitar after a rigorous tour of duty in piano lessons. He eventually went AWOL on the piano lessons, but in the end could play the Star Wars theme beginning to end, which was about the coolest thing in the world. But none of us were trying to write songs together.

Roadies for a Teenage Funeral

Then, on July 7, 1990, our good friend Danny Tonjes—then 15—along with another kid, Chesare “Chaz” Clairbois, 17—were run down and killed by 22-year-old Donald Eugene Green. Green was drunk, and in the end skated on two manslaughter charges in addition to leaving the scene of an accident. Danny was the wildest kid we knew. He was a funny, loud, talented drummer who played in marching band. He was tallest among us, prolific cartoonist and comic book collector, and could belch the alphabet. Danny introduced me to Public Enemy. When the adults broke the news Danny had been killed, we rode our bikes out to the spots where he’d been hit and where his body landed and kicked at the fragments of plastic and metal along the busy shoulder of Hwy. 17-92, wondering if any were artifacts of the accident itself.

In the week leading up to the funeral something happened that had never happened before. Bryan, Ryan, and I holed up in my bedroom and wrote a song. We had a RadioShack cassette recorder and a guitar amp with a habit of picking up evangelical AM radio broadcasts. We used a second tape deck to sample the preacher. When we recorded the song we wrote, the only vocals were the static-fuzzed preacher, the only fragment I remember him saying ending with “…and then I want to ask you a question.”

As it happened, we were enlisted as roadies for the funeral. Danny’s older brother, Nate, and presumably his parents, Sharon and Steve, wanted music. They requested Ben E. King’s recording of “Stand By Me,” and Nate told us he wanted us to “blast the song” at the beginning of the service. I remember it was hellishly hot, lugging those wooden 3-way speaker cabinets into the Methodist balcony. We were and were not at the funeral, in a sense, and it could be we were given the task as a kindness, a protective distance from the raw front row. Whatever communal grief we were there to share was displaced by the physical exertion and surge of adrenaline at being responsible for the music. As people filed in, we timidly played our recording of the song we wrote, immediately recognizing the stereo was underpowered for the church, and then pushed the thing has hard as it would go to play “Stand By Me.” (Only later did it occur to me “Stand by Me” was most recently used in the 1986 film of the same title, an adaptation of a Stephen King story in which a group of boys journey to see the body of a kid killed by a train. I don’t think anyone made that particular connection at the time.1)

Where did our impulse to make music come from? Never once were we moved to write a song together. Never once did we realize we had all the components of an actual band—Danny on drums, Bryan and Ryan on guitars, me on keyboard. Only after Danny’s death did we seem to draw together and write a song.

Some time after, my father asked Bryan and I which songs we wanted played at his funeral. We could each pick one. He informed us he would have the names of the songs added to his will, with instructions to have them played at the service. (As if the man was planning to lie in state!) This didn’t seem strange to us at the time—after all, he was always sick with diabetes and heart disease, the threat of him dying hung over the house all our lives, and who the hell knew how wills worked?—and I suppose it was one of those gestures my father meant to be received as loving consideration. Pull back thirty years and the strangeness shines through: Hey boys, pick your favorite song so you can have it eternally tied to your old man’s death one day! Uh, thanks, Dad? Still, we dutifully complied. I think I might have put in a request for Depeche Mode, my brother for Guns ’n’ Roses.

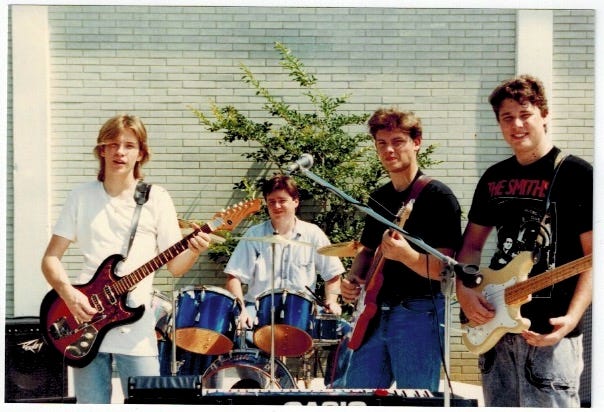

Did Danny’s death wake us to our own musical possibilities? We were the MTV generation, so the mythological lives of rock stars were front and center, but that was like the realm of the gods compared to the regular adult world. Yet over the next few years, Bryan would begin hammering out covers of Fugazi’s “Blueprint” across the street with some neighborhood kids, and Ryan and I would go on to join our friend Chris to form the core of our own high school group, playing suicidally unpopular covers of Joy Division’s “Day of the Lords” and New Order’s “Ceremony” alongside our own tormented originals. Despite being overshadowed by the torrential popularity of hardcore and all the kids savvy enough to play it, we kept throwing our reverb-drenched sad kid songs at anyone tolerant enough to let us plug in our gear.

[Photo from our first high school gig. L-to-R: Keith, Chris, Ryan, & Eric (The Smiths t-shirt). See also: “Acid washed cargo shorts are what I wear on the outside because acid washed cargo shorts are how I feel on the inside.”]

We practiced for hours after school and on the weekends. We burned precious gas money and loaded into any derelict club, strip mall, or pool party to play. We feverishly wrote songs we didn’t have the chops to perform. Were we beloved? No. Not even by 90% of our peers. And those unsuspecting adults ambushed by our gigs did not become fans. Imagine you’re settling into a college football bar in central Florida to watch the Gators battle FSU, only to have four nerdy teenagers ear-fuck you with their interpretation of Front 242’s “Headhunter.” Would you clap?

Yet we persisted under the potent teenage spell of being under-appreciated artistic geniuses surrounded by a culture of savage rednecks and craven sell-outs.

To be fair, we were surrounded by savage rednecks and craven sell-outs.

A Resurrection Bankrolls a Recording Session

In 1992, after a grim year of my father waiting around to die from congestive heart failure, one of his former students referred him to a surgeon in Sarasota, FL willing to perform a risky third open-heart surgery. The odds of success were low, but without surgical intervention, my father was effectively dead. Figuring we were responsible enough to get ourselves to school and not burn the house down, my parents left us in charge for a week.

It’s strange I don’t remember saying goodbye to my dad before he left with my mom for the long drive to the hospital. There was a high probability I’d never see him again alive. Maybe I’d gotten so used to the possibility of him dying that one more roll of the dice didn’t seem like a special occasion. Maybe the prior year had been so miserable, his depression so black, that the prospect of a future without him had begun to feel preferable. More likely, the magnitude of the situation simply overflowed my buffers, locked me out of any manageable connection to my fear or grief.

Because my parents house had no garage, we never practiced there. But once my parents were safely out of range, we pushed all the living room furniture to the margins and setup our instruments for the week. No rager required. We only wanted to jam, making music again in death’s house.

This time the house didn’t win. The surgeon’s gamble paid out a jackpot: Dr. Mike Raymond would live to teach again. High off beating the odds, my father made our band an extravagant offer. Since we believed we merely needed a demo tape in order to secure better gigs and solicit record labels, he offered to pay for studio time so our band could cut a “professional” album. We didn’t even have to pay him back. This from a man so cheap, when asked what he would do if he won the lottery, he mused, “buy a new boom box and a couple of nice shirts.”

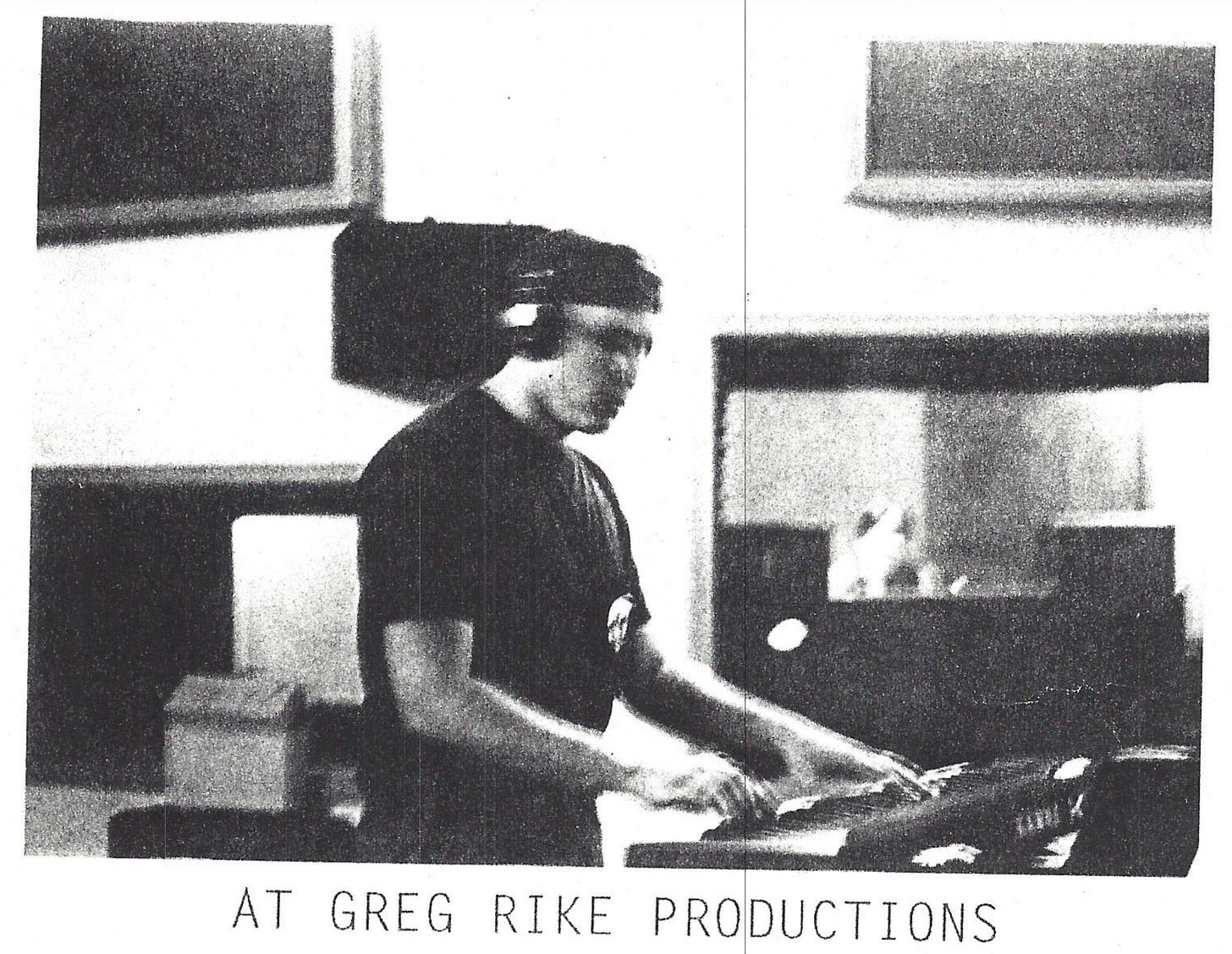

But the resurrected man made good on his offer. He forked over the unthinkable sum of $1,000 so we could book 20 hours at $50-an-hour with Greg Rike Productions Altamonte Springs, FL. Four hours a day—Monday through Friday for one incredible week in July—we had our own engineer, console, and 16-track AMPEX reel-to-reel. Everything about the experience was as pro as you could hope for—save the musicians.

[Portrait of the writer as a teenage synthesist. Photocopied B&W recording session photos were de riguer for indie press kits in the 90s.]

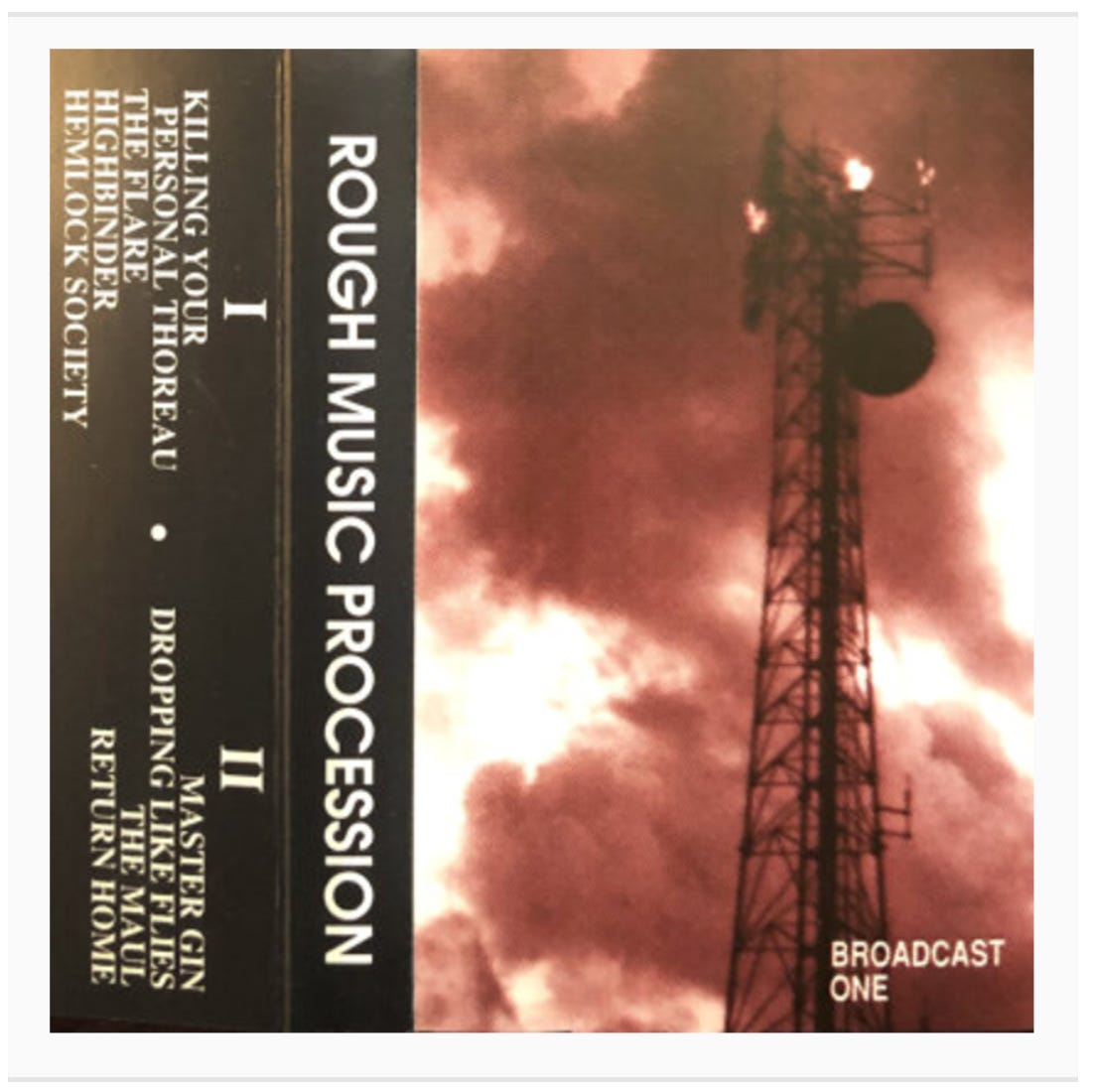

The Release of BROADCAST ONE

And so in 1993, our band Rough Music Procession (yes, really) released BROADCAST ONE in a conservative run of 250 cassettes. Featuring such burners as “Killing Your Personal Thoreau,” “Hemlock Society,” and “The Maul,” it is a cryptic, death-soaked, quasi-concept album dripping with our goth/industrial/prog-rock influences, wobbling unevenly at times out of its despair and rage towards anthemic, post-apocalyptic fantasies of being the last human on Earth. (A depopulated planet was just enough space for our egos.)

I may drag those angsty adolescents with all my adult perspective, but I also know that within our pretensions and delusional hope we were parsing our growing sense of powerlessness. The first Gulf War had kicked off. Our friend was dead, the killer drove away. Everywhere there was no justice. Despite being the son of a professor, I had no desire to go to college. Our post-high school future did not seem promising. It’s all right there in the first line of the first track:

“By the station side / lies the broken dawn / like the body of / the trainstruck boy.”

Despite tireless self-promotion, including one rigorously scripted gig involving fog machines, lasers, pre-recorded video and narration, all played to a substantial crowd of friends from the balcony of our town’s only indie record store (R.I.P., Side One Records) we did not emerge the darlings of Matador or Dischord. Rough Music Procession broke up, was resurrected briefly as Between the Black Machines, then succumbed to disharmony and departures. I ended up taking the faculty brat free ride at Stetson University and quit making music in favor of writing. Poems were solitary, lyrics free from the compromise and conflicts of musical collaboration. Let the ferrous-oxide on all our unsold cassettes decay in dark closets, get lost, get tossed. What else was a garage band supposed to do, if not help you survive high school? The final track on the tape was “Return Home,” and seemed to forecast all inevitable conclusions in the song’s last lines:

“Broadcast One / exploding sun / the end from which we’ve idly run. / I’ll transmit now my life and death, / but the air just runs out so fast.”

UPDATE: After some negotiations and deliberation, Ryan and Chris have allowed the final track (“Return Home”) to be embedded here:

Dead Dads & Digital Time Capsules

I thought BROADCAST ONE was lost to time, but it turned out that our drummer, Chris, had the DAT transfer from the AMPEX master. We couldn’t afford to buy the AMPEX, but Chris’ parents paid for the DAT copy. Through a sound engineer friend, Chris arranged for encoded MP3s of the songs. It was also Chris who—working for Microsoft right around 2002—called me up while I was playing poker in Las Vegas to hire me to write music for their PC games demo reel that year for E3. I had no business doing it, but his faith in me was heartening. My father’s legs had recently been amputated below the knees due to diabetic complications and—coincidentally?—I was flirting with music once again. I dutifully produced tracks, and maybe a third of them were viable.

Chris’ father, Larry, was unexpectedly the first of the dads to die. Chris’ parents bore the brunt of our practice sessions in their garage. Larry played in a country bar band as a hobby, a very “I Left My Ex in Texas” reason to drink on Thursday nights, and would drift into the garage from time to time smoking a cigarette to deliver a bone-dry assessment of our latest composition, his bemused insults undercut by the generous gift of free practice space and forbearance. We only wrote one song which he admitted to liking (“The Maul”), and mentioned how in the hands of more capable musicians, it might actually be good. (I could never fathom why that song, as it was our muddy, moody dirge, dredged out of our adoration of The Cure’s Disintegration.)

Ryan, our guitarist and vocalist, passed me the MP3s of BROADCAST ONE just this year. We’d connected regularly again after his father’s funeral. Ryan’s father, “Bob” was a towering figure in my life, with influence near equal to my own father. Bob was the last of the dads to die in 2022, with my own taking second place in 2007, a full 15 years after his final open-heart surgery.

[Flattened J-Card insert from the cassette release.]

And so, a full 30-plus years after recording BROADCAST ONE, the songs emerged again like some Napster-ripped time capsule. The salvaged album has been my soundtrack as I’ve written this essay. It’s strange to hear your own early music as a stranger, to not have a memory of how a song sounded that you used to play, but to suddenly have it light up all these dormant neural networks. Unlike a diary, the songs forge a direct emotional connection, unmediated by language. It’s an unexpected gift as I’m closing in on my 50s to tap into a raw record of what it sounded like to be a bunch of creative kids coming up on their 20s.

What is there to hear? Though the studio pitilessly records our mistakes—missed beats, wavering vocals, slightly sour tunings, sloppy keys—it also makes me feel tender for the bunch of us as a band. We stayed true to who we were, trying our best to express what we felt without much consideration for an audience or a market. Though derivative at times, we tried to pull off something ambitious in our arrangements and instrumentation. The ideas weren’t all bad so much as we didn’t know how to achieve them technically. The lyrics were obtuse juvenilia at their lowest, but reasonably poetic at their heights. Add to this the fact that we were all of 16 and 17 years old and hadn’t written a single original song with another person until three years prior.

We had horsepower and a slippy transmission. We were of an age, in a place, where there seemed like there was no escape. What could we say? We needed music when the words hit their limits.

Burn Out, Log Off, Tune In

Music may be the form of art best suited for meeting loss on its own terms. No denials, no deceptions, no descriptions. It mirrors or mitigates grief as needed. It can both strip you bare or shelter you.

When my wife Kim died after a long period of caregiving, I felt a dormant itch to make music. I resisted it for a long time, hanging it on a midlife crisis, on fatigue over failure to thrive as a writer, despite my faith in its value. But the tyranny of identifying as a writer—of forcing my hand as a novelist above all other forms of art—had begun to fail me spiritually. It didn’t help to hear how all the world seemed exhausted of novels. It didn’t help to see how moribund mainstream publishing subsisted on a steady diet of celebrity brands, self-help, reheated IP, politically opportunistic trend chasing, and MFA nepo favors. Was I shirking my creative calling by making music, or was I honoring my spirit by moving on? How had all the discipline and control served me?

Given that Kim’s death released me from spending thousands of dollars a month on insurance and home health aids, I decided I would allow myself an exploration of this impulse to let some other artistic desire resurface. What, after all, had I really accomplished as a writer? How much more did I have to say?

As an artist, it’s expedient to define yourself in narrow terms for the sake of a market. Specialization and focus helps label and commodify you. It helps you explain yourself to others. But specialization can be a trap. When we’re young and nobody, we’re willing to follow any form of expression which seems to suit our feeling. When we’re old and have become nobody, we should have the courage to abandon ideas of ourself in favor of expression and exploration above all.

I love literature, but the “lit community” is largely uninteresting to me now. Writing remains interesting, but real artists can be harder to find among the literary life coaches and careerists chasing prestige positions, busy currying favor with all these dying institutions. The institutions of the music world died some time ago, and so the independent spirit there is more advanced, the community between artists, artisans, and hobbyists seemingly more open and vibrant because they have had longer to find their way in the modern afterlife of a dead industry. And as language is further debased, abused and divorced from meaning by politicians and corporations, music retains a direct connection to emotion, ever more felt than comprehended.

I’m sorry. This is a long way to come without any conclusions.

To the young versions of ourselves, we might say “you weren’t good, but you weren’t wrong.”

To the versions we’ve become, we might need the courage to say, “you got good, but you weren’t right.”

Where’s the music coming from? I don’t know. Where it always does, I guess? The beginning and the end of the story.

…

BONUS TRACK: “The Flare,” probably the song that reveals how much The Cure and Joy Division held sway:

Update: My memory here may be faulty. It could have been “Lean On Me” by Bill Withers we played from the stereo. But it’s interesting how my mind may have well substituted “Stand By Me” in some grasping at pre/teenage friendship.

I looooved this essay so much. When I wasn't crying (a very good sign), I was laughing my ass off. Judy

"The noise was so powerful it was almost a smell."

!!!!

An incredible line. A beautiful essay.

Now let me hear me the cassette.